Up: Glassmaking

Glass & Glass-Making

8 of 28

|

|

| |

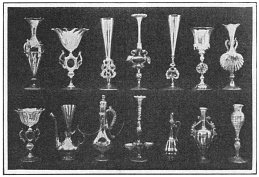

VENETIAN GLASS (16th century)

|

lapis lazuli (lazurite

stone, also called blue spar).

Crusaders often brought home specimens, taking

care to fill them with earth from the Holy Land, which kept them from

breaking and, besides, made them more precious. The famous "Luck of

Eden Hall" is one of these.

The industry suddenly ceased when

Tamerlane captured Damascus (about

1370) and took the glass-makers to Samarkand. In

after years travelers spoke of the gorgeous glass they saw there. This

ware continued to be made in a few places; but it was finally surpassed

by the vogue of the new Venetian "cristallo."

Venetian Glass

Venice had glass-making under artistic control

at a very early period. An old writer, Carlo Marin, said that "Venice

loved the art of glass-making as the apple of her eye." And he was

right. Venice not only took pride in this industry, but it was one

important source of her vast wealth.

The Venetians ceased to make enameled glass after

the Arabian style at the beginning of the sixteenth century; for they had

learned to make an absolutely colorless and transparent glass, capable of

being blown to

A DUTCH SEA-GREEN

GOBLET

Decorated by Anna Visscher.

In the Ryks Museum,

Amsterdam

|

the thinness of a wafer and of being worked into every

variety of form. Everybody wanted specimens of the thin, airy "metal,"

blown into lovely shapes and fantastically decorated with flowers,

sea-horses and dragons with spreading wings, or exhibiting spiral lines

of milk-white, or colored threads.

The artistic beauty of Venetian glass, made in

Murano (an island near Venice), depends entirely on the skill of the

glass-blower rather than on that of the enameler, engraver, or cutter.

The Murano workmen sought perfection of form, delicacy of color and the

fairy lightness of the soap-bubble.

This exquisite glass was imitated everywhere,

until it was pushed aside by Bohemian glass. Murano glass-making was

revived in 1856 by Dr. Antonio Salviati,

a prominent lawyer of Venice, who gave his time and fortune to the

restoration of an art that was not dead, but sleeping.

|

|